Saint Paul Bread Club

We knead to bake!

Page Menu

Other Links:

Oven Types

There are several types of ovens in modern use. I mention some sources here, but you should look at the Oven Sources and Oven Links for more complete information.

How Ovens Are Built

Ovens have an ancient history. Ovens built in the modern day tend to be of a few different kinds. (This is pretty much regardless of who builds them.)

- A single cast piece of refractory concrete.

- A single prefabricated oven unit.

- Multiple prefabricated ceramic parts.

- Hearth slab and fire brick.

- Hearth slab and cob (clay).

- Stacked bricks or dry-laid stone.

Ovens that are expected to be built by hobbiests and home builders tend to be of simpler design and construction than those in use commercially.

Commercial ovens might be prebuilt, built by master masons, or even built by imported oven setters. (These tend to be for high-end restaurants.)

The Hearth Slab

A lot of thought needs to be given to the hearth slab, since for most ovens this is where the fire is built and where the cooking and baking are done.

In many cases the hearth slab may be built in three layers. From bottom to top these would be:

- Structural layer (responsible for holding up the whole oven, effectively the top of the base.

- Insulating layer (responsible for keeping the heat in).

- Oven floor (responsible for retaining heat and doing the actual cooking and baking).

There are many choices to make for each of these layers.

Structural Layer

This is usually made from structural concrete reinforced with “rebar.” Depending on the oven design, this could be the base of a “floating slab” or it could be rigidly attached to the walls of the base of the oven.

The thickness of this layer depends on the structural load it needs to support.

Insulating Layer

This is sometimes made from insulating refractory, either from a commercially available premix, or by adding insulating material to a commercial concrete mix.

Another alternative is to use FOAMGLAS.

The thickness of this layer depends on how much insulation is required for the type of oven being built. (A thickness of 2.5 inches is a frequent minimum.)

Some cob oven designs use empty wine bottles, perhaps embedded in vermiculite, as an insulating layer.

Oven Floor

This layer is often made using firebrick. Depending on the design, there could be one layer of firebrick 2.5 inches thick, two layers of firebrick 5.0 inches thick, or one layer for firebrick turned on its sides, 4.5 inches thick.

These bricks are not mortared together; they are just placed very carefully and closely together.

How the oven is heated

There is also a question about whether the oven is a “white oven” or a “black oven.”

This is a distinction seldom drawn because most people never care about it.

- A white oven has the firebox separate from the baking chamber, and the fire can be going while the oven is in use. (The fire can be an active heat source.)

- A black oven has no separate firebox, so the baking chamber gets a certain amount of soot and ash from the fire. The fire is usually removed and the hearth cleaned before baking to keep the ash off of the baked goods. If the oven is used for pizza, a fire might be maintained around the edges or in the back to keep the oven hot during baking. (Since the heat comes from where the fire had been, these ovens are also sometime called retained heat ovens.)

Most oven plans that individuals build for themselves are black ovens.

Scotch Ovens

One of the common styles of white ovens that used to be built is called a Scotch oven.

I have found a few links about Scotch ovens, including a bakery in Australia that was brought back as a commercial enterprise after long disuse.

How Ovens Are Used

One key question you need to know before you build or buy an oven, is, “How you are going to use it?”

- Bread oven

- Pizza oven

- Both

A bread oven needs to hold heat for a long time, but has a lower operating temperature than a pizza oven. A pizza oven at 800 degrees can cook a pizza in 90 seconds. A bread oven is better at 350 to 450 (although some breads, like thin baguettes, can be baked as hot as 600 degrees).

Oven management, where you learn to bake the right things at the right temperature, is one of those skills that you must learn to successfully operate a brick or cob oven.

In general, bread ovens have more mass, take longer to heat, and keep their heat longer as well.

A pizza oven may also be designed to keep a fire going on the inside as long as pizzas are being baked; this helps maintain the temperature.

How the oven is intended to be used will often decide one of the important factors in the oven design: Will the oven be low mass or high mass?

Low Mass

A low-mass oven is one that has comparatively thin hearth and walls, resulting in comparatively low thermal mass. This means that the oven will heat quickly, but also that it will cool off quickly.

Such ovens tend to be big enough to maintain some active fire inside while the rest of the oven hearth is used to cook food at a comparatively high temperature (650 degrees F. and higher).

These ovens are often used for pizza.

As long as wood is thrown onto the remaining fire, the oven will stay hot, up to several hours.

Such ovens may have a lot of insulation if they are intended to used commercially, since the added insulation makes them more fuel efficient.

High Mass

A high-mass oven is one that has comparatively thick hearth and walls, resulting in comparatively high thermal mass. This means that the oven will heat more slowly, but it will also cool off slowly.

Such ovens tend to be used for bakery operations. Some such ovens will be fired for 6 to 8 hours, and then used to bake for 6 hours (at gradually declining temperatures).

Common Features

For wood-fired ovens, there are some common features that sometimes take people by surprise.

Where is the chimney?

In wood-fired ovens, the chimney is outside of the oven itself. It will often be placed outside the oven door, but between the oven door and the front facing of the oven. That’s because when the fire is burning inside the oven, the circulation of hot air is forced to go over the entire oven ceiling and then out the door of the oven. Directly venting the oven interior would just result in heat being lost.

In some designs, there is no chimney. The venting is done through the oven door. That simplifies the design, but it does lead to soot buildup on the outside of the oven. Combustion is also not as clean as it could be.

A traditional (that is old) oven design called a squirrel tail oven would route the the exhaust out the back and over the top of the oven (much like how a squirrel will cover its back with its tail).

These were more complex to build, but not without their advantages.

Where is the ash dump?

A wood fire produces ash. It has to go somewhere, and you want it out of the oven if you are baking directly on the oven floor. Often there is an ash dump slot just outside the oven door (about where the chimney is). A metal trash barrel can be placed underneath to collect the hot ash as it is raked and brushed out of the oven when the fire is done and the oven is ready to be used.

What kind of roof?

An outdoor oven is a kind of building, one that would suffer degradation from the elements. For this reason, outdoor ovens often have roofs. There is no standard for the roof type, but can be a shed roof, an A-frame, with or without a substantial overhang (for protecting the bakers).

It is one of the elements where costs and benefits need to be considered when planning an oven.

How high should the oven floor be?

This doesn’t get discussed much, but this is actually an ergonomic issue in tension with a cost issue. There must be some kind of base for the oven. This serves as part of the thermal mass of the oven. It can also be used for fuel storage, and as part of the ash dump. (See the pictures of the different private ovens for some examples.)

Generally you want the floor of the oven to be about waist level, so that you can use a peel to get bread into and out of the oven with the least amount of strain on your back and arms.

The cost of the height of the base is partly based on the volume of material that it takes to build it. Kiko Denzer has several ideas on how to find material to use for little or no money. If you want to take the direct approach, concrete blocks are often used for the base.

For the home builder, the base represents a significant investment in time, labor, and materials (and therefore cost). Because ovens weigh so much, you have to decide what kind of base you want before you build your oven.

How high should the oven roof be?

There is not a lot of advantage to having a tall oven; since heat rises, and most of what you bake will be on the hearth floor, an oven that’s too tall will be a waste of energy. Typical ovens for bread might be 14 to 18 inches high in the middle of the dome or vault, and 9 inches high on the sides.

Concrete Ovens

The only source I know for prefabricated refractory concrete ovens is here in Minnesota: Artesian Ovens.

(There might be others, but shipping such large and heavy items would tend to make them uneconomical.)

Prefabricated Ovens

There is one source I have found for an entire oven: Vesta Fire USA

It is a stainless steel enclosure around a fire brick interior. This is for a pizza oven that can operate at temperatures of up to 950 degrees.

Prefabricated Ceramic Parts

There are three sources of these that I’m aware of. (You would need to determine for yourself how to get these ovens installed for you, because I don’t know.)

Apparently one of the advantages of the ceramic ovens is that they use less fuel than a brick oven because of the nature of the ceramic. (I don’t know how to verify that claim, but it’s worth considering.)

Brick Ovens

See also:

- Brick Oven Links

- Individual Brick Oven Project Links

- Stacked Brick Oven Links

- Temporary Brick Oven Links

For ovens built from brick, there are designs that are merely a careful stack of bricks (as few as 100 and as many as 500), domes (a traditional Italian style) and barrel vaults (many of which are known as Alan Scott designs, since he was most well-known modern proponent, designer, and builder of such designs).

There can be a lot of parts that go into building a brick oven. If you can salvage any of the parts, you can reduce the construction cost. Expect parts costs to be $2000 to $5000 (or more depending on the size of the oven and complexity of the shelter for it).

For the better built brick ovens, just the hearth slab can be three layers of different materials that make the oven more efficient.

There is also an interesting range of complexities of brick oven. Some are, shall we say, a bit more crude than others.

Some points along the spectrum of crude to fancy:

- DIY Brick Pizza Oven (pretty crude)

- DIY Brick Oven 2.0 (less crude)

- The 1-Hour Brick Oven (from clever to pretty clever)

- Participants’ Ovens (a nice variety of medium-sized ovens)

- Mary G’s Artisan Breads Traditional wood-fired brick-oven (extreme)

- 60 Ton Oven (even more extreme, but no picture)

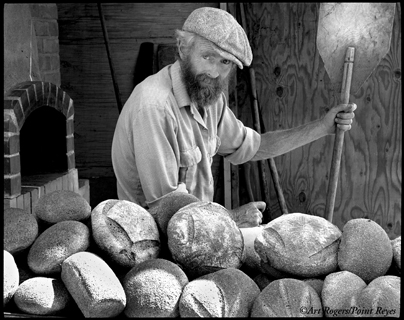

Photo of Alan Scott used with permission of the photographer, Art Rogers.

Cob Ovens

See also: Cob Oven Links

Cob ovens are in some sense individual works of art. They are much cheaper to build than brick ovens. In the right environment, they can be built entirely from materials available on-site.

- Sand

- Clay

- Straw

- Rock (or brick)

For this reason, there are many garden ovens that are built from cob, because all of those materials might be found around a major garden. (Look in the Cob Oven Links for Cob Ovens in Gardens for some links. You can also go to Google and search for 185,000 links that might be appropriate.)

Cob can be used to build structures other than ovens; look in the Cob Construction Links for more information on cob construction.